When my grandmother, Dorothy Hale, passed away, I believed the hardest part would be letting go of her house.

I was wrong.

At the time, I thought grief was supposed to arrive all at once, like a wave that knocked you down and left you gasping. Instead, it came quietly, in pieces. It settled into corners. It waited in doorways. It hid behind one locked basement door I had been forbidden to touch my entire life.

If someone had told me a year earlier that my future would unravel into a kind of emotional investigation, one centered on my grandmother of all people, I would have laughed. Dorothy was predictable. Steady. The kind of woman who labeled her spice jars and folded towels the same way every time. Secrets did not belong to her.

Or so I thought.

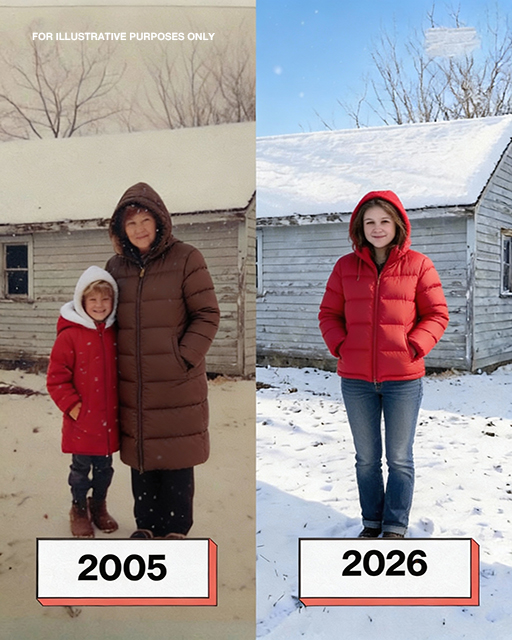

Dorothy had been my entire world since I was twelve years old.

I never knew my father. My mother died suddenly in a car accident when I was still young enough to believe she might walk back through the door if I waited long enough. After the funeral, after the casseroles stopped coming, and after the adults lowered their voices whenever I entered a room, Dorothy simply packed my clothes into two suitcases and brought me home.

No questions. No hesitation.

Her small house at the edge of town became my refuge. I learned how to survive there. How to grieve. How to keep going when your chest feels hollow.

Dorothy taught me practical things: how to bake an apple pie without burning the crust, how to balance a checkbook, and how to look someone in the eye when you said “no” and mean it. She was strict but fair, affectionate in a quiet way, and deeply private.

She had only one absolute rule.

Never go near the basement.

The entrance was outside, behind the house, just past the back steps. A heavy, rusted metal door sat flush with the foundation, always padlocked. I never once saw it open. As a child, the locked door felt magnetic. I imagined pirate treasure, or maybe a hidden room from some forgotten life.

“Grandma, what’s down there?” I asked once, crouched beside the steps.

Dorothy didn’t raise her voice. She didn’t scold me. She simply said, “There are old things down there you could get hurt on. That door is locked for a reason.”

End of discussion.

I learned quickly that pushing further would get me nowhere. Eventually, I stopped noticing the door altogether. It faded into the background of my life, just another piece of the house.

Years passed.

I went to college, came home on weekends, and eventually moved in with my partner, Miles Carter, in a small apartment across town. Dorothy was still there. She was slower now, more tired, but steady. Until she wasn’t.

At first, it was small things. She forgot appointments. She stopped humming while she cooked. Sitting on the porch became “too much trouble.” When I asked if she was feeling all right, she waved me off.

“I’m old, Lena,” she said. “That’s all.”

But I knew her, and I knew something was wrong.

The phone call came on a Tuesday afternoon while I was folding laundry.

“I’m sorry,” the doctor said gently. “She passed peacefully.”

Miles held me while the truth settled into my bones. We buried Dorothy on a cold, windy Saturday. After the funeral, distant relatives offered condolences and advice in equal measure.

“Do whatever you think is best with her things,” they said.

So, a week later, Miles and I drove out to her house to pack it up.

The place felt frozen in time. Her slippers sat beside the couch. Her faint, familiar scent lingered in the air. Every room carried a memory.

We worked slowly, sorting through decades of life. Old photos. Handwritten recipes. Cards I had made as a child. By late afternoon, I found myself standing in the backyard, staring at the basement door.

For the first time, there was no one to stop me.

“Miles,” I said quietly. “I think we need to open it.”

He hesitated, then nodded.

Breaking the lock felt like crossing a line. The metal snapped with a harsh sound, and when we pulled the door open, cold, stale air rushed out. Miles went first, his flashlight cutting through the darkness. I followed, my heart pounding.

The basement was small and meticulously organized.

Along one wall stood rows of boxes, all neatly stacked and labeled in Dorothy’s handwriting. Miles opened the closest one.

On top lay a tiny, yellowed baby blanket. Beneath it were knitted booties. Then a photograph.

It was Dorothy, young and frightened, sitting on a hospital bed. She couldn’t have been more than sixteen. In her arms was a newborn baby wrapped in that same blanket.

The baby was not my mother.

I don’t remember screaming, but Miles says I did.

The boxes told a story Dorothy had carried alone for more than forty years.

There were photographs. Letters. Adoption paperwork stamped CONFIDENTIAL. Rejection notices. And then, at the bottom of one box, a thick notebook.

It was filled with dates, agency names, and short, devastating notes.

“They won’t tell me anything.”

“No records available.”

“Told me to stop asking.”

The final entry, written just two years earlier, read:

Called again. Still nothing. I hope she’s okay.

My grandmother had given birth to a baby girl as a teenager. She had been forced to give her up. She had spent her entire life trying to find her.

In the margin of the notebook was a name: Marianne.

I sat on the basement floor and cried until my chest hurt.

“She carried this alone,” I whispered.

Miles squeezed my hand. “But she never stopped looking.”

We brought everything upstairs. That night, I made a decision Dorothy never could.

I was going to find her daughter.

The search was exhausting. Records from the era were scarce. Agencies refused to help. I signed up for a DNA database out of desperation, not hope.

Three weeks later, I received an email.

A close match. A woman named Marianne Brooks, fifty-five years old, lives less than an hour away.

I sent a message with shaking hands.

The reply came the next morning.

I’ve always known I was adopted. I’ve never had answers. Yes. Let’s meet.

We chose a quiet café halfway between our towns. I arrived early, twisting a napkin into shreds.

When she walked in, I knew immediately.

She had Dorothy’s eyes.

We talked for hours. I showed her the photo, the notebook, and the letters.

“She searched for you her whole life,” I said.

Marianne cried quietly. “I thought I was something she buried.”

“She never stopped,” I told her. “She just ran out of time.”

When we hugged goodbye, it felt like closing a circle that had been open for decades.

Dorothy’s secret was finally free.

And in finding Marianne, I realized something else.

Some doors are locked not to hide shame, but to protect a love too painful to lose.

Dorothy never stopped being a mother.

Neither did I.