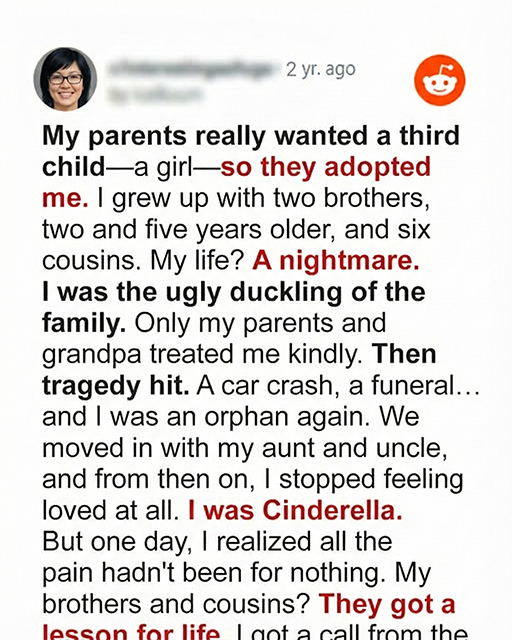

I was three years old when my parents adopted me, though that fact followed me through life like a label stitched too tightly into my skin—always there, always rubbing.

For years, my parents had tried to have a third child. They already had two sons, loud and inseparable, and they dreamed of a daughter to “complete” the picture. When the adoption agency finally called, they drove four hours without stopping, afraid that if they slowed down, the universe might change its mind.

They named me Maren.

From the outside, we looked like a storybook family. A white fence. A tidy lawn. Two older brothers—Cole and Brandon—and a little girl with dark curls and hopeful eyes. People smiled when they saw us at the grocery store. Strangers said things like, You’re so lucky or What a beautiful family.

Inside the house, though, the walls heard different words.

Cole was five years older than I, and Brandon was three. They learned early how to speak softly when our parents were around and sharply when they weren’t.

“You don’t really belong here,” Cole whispered once while we were supposed to be cleaning our room.

Brandon laughed. “Yeah. You’re just… borrowed.”

At first, I didn’t understand what that meant. I only knew that the tone made my stomach hurt.

As we grew older, their words sharpened.

“You’re not blood.”

“They picked you because they felt sorry for you.”

“You’re the reason Mom’s always tired.”

I tried to be perfect after that. Quiet. Helpful. Invisible when necessary. I folded my clothes the same way my mother did. I memorized where everything went in the kitchen. I learned how to sense moods the way some people learn to read maps.

It didn’t help.

Family gatherings were worse. Our cousins—Lydia, Harper, Owen, Miles, Tessa, and Rowan—took my brothers’ lead like it was a game with rules they already knew.

They teased me about not having baby pictures.

They asked where my “real parents” were.

They laughed when I didn’t know the answers.

The adults pretended not to notice. Or maybe they truly didn’t. Aunt Celeste spoke to me politely, like I was a neighbor’s child who’d wandered into the wrong house. Uncle Raymond rarely looked at me at all. Once, I heard a neighbor refer to me as “the adopted one” in a whisper that was meant to be kind but landed like a bruise.

The only person who ever made me feel like I wasn’t a mistake was my grandfather, Arthur.

He smelled like pipe tobacco and garden soil, and his laugh came from somewhere deep and solid. He never treated me differently—not in the careful way, and not in the cruel one either.

He taught me how to fish, how to knead bread until the dough felt alive, and how to sew a button back on without swearing too much. When cousins cornered me at birthdays or holidays, he always seemed to appear between us, his hand settling lightly on my shoulder.

“That’s enough,” he’d say, calm but immovable. “Go on now.”

Later, he’d sneak me a cookie or a piece of pie and tell me stories about his childhood—about how love didn’t always come from where you expected, but it always left marks if it was real.

For a while, that was enough to keep me going.

Then I turned eighteen.

My parents were driving home from a short weekend trip they’d planned months earlier. It was raining—one of those cold, steady rains that blurs the road into a single sheet of gray. A truck ran a red light.

There was no warning. No goodbye.

Just absence.

The funeral passed in fragments: black umbrellas, murmured condolences, people squeezing my hands and then letting go too quickly. I stood between Cole and Brandon, and neither of them reached for me. I didn’t cry, not because I didn’t want to, but because my body felt hollowed out, as the tears had nowhere to land.

Someone whispered that I was “strong.” Someone else said I was “cold.”

No one asked how it felt to lose the only people who had chosen me.

Afterward, Celeste and Raymond were named our guardians. Within a week, I was living in their house, sleeping in a spare room that smelled faintly of dust and old detergent.

They didn’t hide their resentment.

I cleaned. I cooked. I folded laundry that wasn’t mine. I learned which floorboards creaked and which didn’t. I spoke only when spoken to.

If I forgot a chore, Celeste snapped. If I tried to join a conversation, Raymond changed the subject. The cousins visited often, and their m.0.c.k.3.r.y followed them through the door like an old habit.

“Still pretending this is your home?”

“Ever wonder why your real family didn’t keep you?”

At night, I cried quietly in the garage, sitting on a cold concrete floor so no one would hear me.

Grandfather Arthur still called, still checked in, but his voice was slower now. His hands shook sometimes. He couldn’t be everywhere, and I never asked him to be.

I thought that was how my life would stay—small, contained, survivable.

Until one Tuesday afternoon, while I was folding towels, my phone rang.

The number was unfamiliar.

“Hello?” I said cautiously.

“Is this Maren?” a man asked.

“Yes.”

“My name is Victor Salgado. I’m an attorney. I’m calling regarding the estate of your biological aunt, Helena. She passed away recently.”

I almost laughed. I’d heard worse pranks.

“She left you something,” he continued. “But you were… difficult to locate.”

“I’m sorry,” I said. “You must have the wrong person.”

“I don’t,” he replied gently. “She left you a private inheritance. Three million dollars.”

The towel slipped from my hands and hit the floor.

Three million dollars. A will. Someone who had been looking for me.

I flew out the following week. Victor met me with kind eyes, a stack of documents, and a sealed letter in a pale blue envelope.

Everything was real.

Helena had left me her coastal house, her savings, her journals—and the letter.

Maren,

You were never meant to disappear.

She wrote about my birth parents—young, frightened, unprepared. About how her family insisted adoption was best. About how she’d been told to let go.

She never did.

I looked for you quietly for years, she wrote. I didn’t want to arrive too late and cause harm. This is me arriving now.

I read the letter until my hands stopped shaking.

The next day, I packed my things. I left a note behind. No explanations. No apologies.

The only person I asked to come with me was Grandfather Arthur.

He smiled when I told him. “Took you long enough,” he said. “Now go live.”

The house Helena left me was a blue cottage near the sea, ivy curling along the porch as if it had been waiting.

Arthur and I settled into a quiet rhythm. We cooked together. We talked. We rested.

One evening, while we prepared dinner, he asked casually, “Have you thought about school?”

I shook my head. “I was busy surviving.”

“That part’s over,” he said. “Now you get to grow.”

After a long silence, I told him what I’d been afraid to say out loud.

“I want to go to culinary school.”

He beamed.

Six weeks later, we opened a small coffee shop near the shore. We called it Second Turning.

I enrolled in school shortly after.

The cousins tried to come back into my life when they heard. My brothers called. Apologies floated in with expectations attached.

I declined them all.

One afternoon, Arthur handed me a letter my parents had written years earlier, full of hope and love.

I cried then. Not from pain—but from knowing the truth.

I had been loved. I had simply outgrown the cruelty.

That night, I lit a candle for Helena, baked cookies, and played one of her records.

I wasn’t waiting to be chosen anymore.

I had chosen myself.